My ramblings about Panglong would have been incomplete without babbling anything about the subject tabooed in Burma: The Right of Secession.

Young people would ask me why they never saw any clause mentioning the right of secession in the text of the Panglong Agreement, although according to singer Sai Hsaimao’s Promises of Panglong, the Shan State was supposed to have been allowed by the agreement to exercise this right after ten years.

The reason, as contemporaries have recorded, was that the two sides had reached a gentleman’s agreement that the right to secede from the Union would be incorporated into the then yet-to-be-written constitution. And as the agreement was concluded at Panglong, it has always been associated with the Panglong Agreement although the treaty itself utters not a word about it.

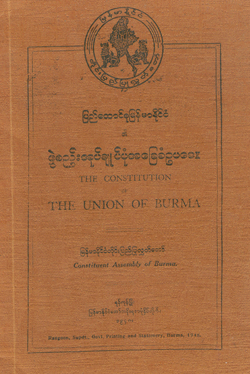

Aung San, true to his reputation, kept his word. The following is the text of the right that appears on Page 56:

CHAPTER X.

Right of Secession.

201. Save as otherwise expressly provide in this Constitution or in any Act of Parliament made under section 199, every State shall have the right to secede from the Union in accordance with the conditions hereinafter prescribed.

- 202. (1) Any State wishing to exercise the right of secession shall have a resolution to that effect passed by its State Council. No such resolution shall be deemed to have been passed unless not less than two-thirds of the total number of members of the State Council concerned have voted in its favour.

(2) The Head of the State concerned shall notify the President of any such resolution passed by the Council and shall send him a copy of such resolution certified by the Chairman of the Council by which it was passed.

204. The President shall thereupon order a plebiscite to be taken for the purpose of ascertaining the will of the people of the State concerned.

205. The President shall appoint a Plebiscite Commission consisting of an equal number of members representing the Union and the State concerned in order to supervise the plebiscite.

206. Subject to the provisions of this Chapter, all matters relating to the exercise of the right of secession shall be regulated by law.

Article 201, in practical terms, means only Shan and Karenni have the right to leave the Union. Others are explicitly denied the right.

However, had the Burmese government and the Burma Army’s treatment of the non-Burmans been exemplary, there would have been nothing to fear about it. Aung San himself had said, “The right of secession must be given. But it is our job to see that they don’t want to secede.”

The Burmese government and the Burma Army, unfortunately, had every reason to fear, because they know they had done little “to see that they don’t want to secede.”

And, despite being avowed Buddhists, who are supposed to uphold truth and compassion, they had neither. What they had instead were the un-Buddhistic pride and the belief in force.

According to Sao Man Fa, the late Prince of Monghsu, he was summoned to the office of the Military Intelligence Service (MIS) following the coup in 1962. He was handed a piece of paper and a pen to sign his name. “We hope you will not be pig-headed like the Prince of Hsipaw (Sao Kya Seng, who was detained outside Taunggyi and has disappeared since),” Col Maung Lwin told him.

It was an affidavit saying the signatory was against the right of secession and was committed to remain in the Union forever.

Sao Man Fa did not consider himself a brave man, but he decided that to continue living with himself whom he held no respect would even be more fearful. He therefore refused to sign and chose to spend his life in prison or executed instead.

What I wish to emphasize here is not Sao Man Fa’s courage though he fully deserves it, but the obsession of the military with its fear of the right of secession, amounting to absurdity.

Common sense tells you that when you want someone to live with you, you have to make that someone feel happy with you. But what successive Burmese leaders have done is nothing less than mindless: bully that someone to fear you, then, fearing that someone would hate you and want to leave you, you end up using more and more force, and so it goes on and on.

Like what the Buddhist saying goes: You may forgive someone who wrongs you, but you may never forgive someone whom you have wronged.

But, looking at things as they really are, I don’t see any reason for a Burman leader to fear a plebiscite.

One reason is the ethnic Shan population in Shan State:

1931 census 46.9%

1993 official statement 38.5%

2006 official statement 35.5%

[According to the present government’s predecessor, the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), in Shan State, apart from Shan, there are Yun Shan, Khamti Shan, Gon (Kheun) Shan, Taileng Shan, Tai Ner Shan, Tai Long (Big Shan), Shan Gyi (which also means Big Shan) and Shan Galay (which means Small Shan)].

The second reason is the range of the impact of Divide-and-Rule policies practiced by successive Burmese governments in Shan State. 60 years of the Burma Army presence have certainly opened up huge gaps, hitherto non-existent, among Shans and non-Shans, which need not be elaborated here.

The above mentioned reasons, if not others, say that the pro-secessionists are not going to win even if plebiscites are allowed to hold. Just as in Quebec, they have failed, twice in a row, to secede from Canada.

But, if the Burman/Burmese leaders still want to ensure there is no secession now and ever, I have a fool proof suggestion:

Why not remove “the Defense Services” from the present constitution’s 6th Basic Principle (Page 3) “(f) enabling the Defense Services to be able to participate in the national political leadership role of the State” and replace it with “the non-Burmans/non-Bamars”?

If you still can’t stop these Shan that way, nothing can.