The 1962 coup d’ėtat staged by General Ne Win ended an era of saophalong and mahadevi (ruling princes and princesses) in the Shan states, ushering in decades of repressive military rule in Burma. Like many Shan royalty, Sao Kya Seng, the saophalong of the northern Shan State of Hsipaw, was detained by the authorities. He had been in Taunggyi and was arrested at a nearby military checkpoint. He was never seen again. His last note was a signed letter smuggled to his mahadevi, Sao Thusandi, containing details of his detention and mistreatment in the ba htoo tatmadaw (Burmese military camp).

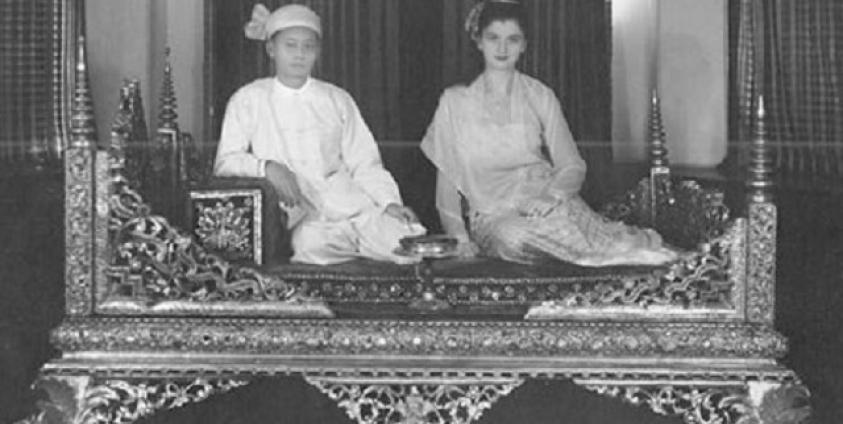

Twilight over burmaTheir story is immortalized by Sao Thusandi, also known as Inge Sargent, in her book, Twilight Over Burma, which was published in 1994. Originally from Austria, she had met and married the prince while both were students in the United States. She was initially held under house arrest before fleeing Burma with her two daughters, Sao Mayari and Sao Kennari, in 1964.

All three now live in the USA and say they have written every year to the Burmese government demanding an explanation to Sao Kya Seng’s disappearance. The family say they have never received the courtesy of a reply. Sao Thusandi once confronted Ne Win himself while he was in Austria receiving psychiatric treatment, personally demanding a response. The dictator’s reaction was reportedly to scurry away from the angry young Austrian woman to the safety of locked doors and armed bodyguards.

Now adapted into a film of the same title, the English-language version was scheduled for a debut screening in Rangoon on Tuesday, June 14th – that was until it was reviewed by the national censorship agency, the Film Classification Board, which includes military representatives and is controlled by the Ministry of Home Affairs. Deemed a “threat to national reconciliation,” it was abruptly banned, a particularly sad irony given that the venue was to be the Human Rights Human Dignity International Film Festival, which counts Aung San Suu Kyi as its patron.

“[It] could damage the ethnic unity of the state,” explained a member of the board, Phone Maw, to the Irrawaddy.

It’s an official response that, while not completely unexpected, reflects a deep structural problem in Burma, speaking volumes about the limits of Burma’s military-guided transition. It is a reaction that is as deeply condescending as it is fatally flawed. At its heart, the unspoken message to many ethnic communities will once again be that accommodating the tatmadaw’s hypersensitive disinclination to even begin to acknowledge its excesses takes precedence over ethnic histories and lived experiences, dismissing and trivializing human rights issues which are ongoing.

While Twilight Over Burma is the first international movie banned under the National League for Democracy (NLD)-led administration, the vocabulary justifying this action, “ethnic unity” and “reconciliation,” and the sentiment behind this reasoning, are nothing new for ethnic communities in Burma, long accustomed to a decades-long pattern of Burman/Buddhist-centric cultural and political homogenization by successive centralized administrations. Until recently, the term “reconciliation” was not even a part of the official (tatmadaw) lexicon, the generals preferring “national reconsolidation”. The implication was subjugation, by force or otherwise, a mindset that continues today.

At its most innocuous, this sentiment manifests in the often patronizing ethnic representations adorning tourist trinkets or at events and venues, particularly those catering to foreigners. At the East Asia Summit in November 2014 held in Naypyidaw, dozens of female ushers in colorful ethnic outfits welcomed world leaders. None were ethnic nationalities. A “Padaung” woman exclaimed to an Associated Press correspondent, “Oh, that’s fake! Did you think I was really Kayan Padaung?”

At its worst, “reconsolidation” entails the deliberate targeting of ethnic communities in Burma by the tatmadaw with human rights abuses against civilians, a campaign of terror against those perceived to be a threat to their notion of a nation-state; in the tatmadaw’s previous lexicon, “internal and external destructive elements” which must be “crushed.”

Since 1996, more than 3,700 villages have been destroyed, relocated or abandoned in eastern Burma, forcing some 400,000 people to live as internally displaced persons, or IDPs. Many others were forced to flee to Thailand, living as refugees or migrants, often without any legal protection. A 2014 Harvard Law School analysis concluded that such pogroms against ethnic Karen communities in 2005-06, which entailed indiscriminate attacks on civilians, destruction of homes and food stores, laying landmines in populated areas, forced labor (including conscripted work as army porters), and arbitrary arrest and executions by members of the tatmadaw, may meet international criteria for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The official response from governments has been a deafening silence. Maj-Gen Ko Ko, the military commander who executed this policy in Karen State, was promoted to lieutenant-general and appointed President Thein Sein’s powerful Minister for Home Affairs until earlier this year.

The NLD administration plans a grand “21st Century Panglong Conference” to address Burma’s ethnic conflicts, implying that Aung San Suu Kyi intends to build upon the uncompleted work of her father, independence hero General Aung San, who convened the first Panglong Conference in 1947, when, in return for joining the Union of Burma-to-be, ethnic leaders were promised the right to autonomy and self-determination. It was a promise never realized, seen in many ethnic communities as an act of betrayal by the Burman-dominated government and military.

If Aung San Suu Kyi is serious about moving forward in the spirit of her father, rebuilding the ethnic trust and rapport that her father enjoyed, equality and an honest reckoning of past mistakes – which continue to be repeated today – must be a cornerstone of her policies. Although over half a century have elapsed since Sao Kya Seng’s disappearance and likely murder, stories such as Twilight Over Burma continue to resonate deeply for many ethnic communities, particularly those who still face the abusive excesses of an unrepentant tatmadaw.

Just ask the families of Lahpai Gam and Brang Yung, Kachin villagers tortured into confessions and arbitrarily detained by the Burmese Army. Or ask the husband of Sumlut Roi Ja, also a Kachin civilian, last seen alive in the custody of the tatmadaw. Or take the case of Ja Seng Ing, a 14-year-old girl shot dead by the Burmese army. When her father had the temerity to petition the president and National Human Rights Commission, he was taken to court by the army for defamation – and found guilty. Or take a look at the tragic events surrounding Maran Lu Ra and Tangbau Hkwan Nan Tsin, two young volunteer teachers in northern Shan State who were brutally raped and murdered in January 2015; evidence strongly implicated a local unit of the tatmadaw, which continues to stymie any independent investigations. Or consider what happened to Sai Aik Naung, Sai Aik Mart and Sai Aik Dink, three Shan villagers last seen alive when they were arrested last month by tatmadaw soldiers in Kyaukme Township, near Hsipaw. Their burnt remains were recovered shortly afterwards.

On a population level, these individual tragedies are amplified a thousand-fold. The perpetrators never have to face justice, thanks to Burma’s military-drafted 2008 constitution.

The Burmese Army’s ongoing impunity for abuses, especially against ethnic civilians, causes the most damage to the image of the tatmadaw and prospects for national reconciliation, not stories such as Twilight Over Burma.

Silence is not reconciliation, it is a time-honored failure which creates instead a collective, myopic, state-directed amnesia dooming Burma to pernicious cycles of hatred and violence. To paraphrase a popular Shan proverb: “The floor continues to be mopped again and again, with no thought whatsoever to repairing the leaking roof.”

Indeed, ongoing official reluctance to broach such sensitive ethnic issues will have dire consequences for reconciliation and a durable peace, further eroding ethnic trust in the NLD leadership. A good start towards breaking this cycle would be to begin honest open discussions about the mistakes of the past and present, particularly at events which promote human rights and human dignity. This would acknowledge and respect the lived experiences of so many ethnic peoples, allowing healing and reconciliation to finally commence. That this has yet to truly occur is only further underscored in the recent decision to cancel the Rangoon screening of Twilight Over Burma.

“Sao [Kya Seng] was always the good Buddhist,” recalled Ms. Sargent. “I was more into the mystical, the fortune tellers and astrology, than he was … I try to be a good Buddhist now. I have been able to let go of the past, but one thing that I can never forgive is Ne Win and the cowards [emphasis is hers] who, to this day, are still too scared to admit to what they have done … The generals believe that just building pagodas and donating to temples will help clean away their crimes, but it won’t. [Until they admit and atone] I cannot forgive them.”

Without closure, she is far from alone