Now that the State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi has officially said that she will lead the legal team to confront the genocide accusation filed by Gambia, a small African nation speaking on behalf of the 57 Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC), all domestic and international eyes are on International Court of Justice (ICJ) hearings which will take place from December 10 to 12.

As all know in 2017, an exodus of more than 700,000 Rohingya to Bangladesh occurred, due to the crackdown which the military or Tatmadaw depicted as “area clearance” arguing it was an undertaking to get rid of Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) members, who attacked some 30 police outposts simultaneously in August 2017 with impoverished weapons using few guns, swords and spears, where 84 were killed including 13 security officials, according to government’s report.

The followup crackdown targeted not only the ARSA members but the whole Rohingya population in the north of Arakan State. And during the expulsion or fleeing of the Rohingya, grave gross human rights violations that could be construed as genocide took place in places like Inn Din and Gu Dar Pyin, killing hundreds, which the government and Tatmadaw now acknowledged that have always been denied, according to Fortify Rights reiteration of the episodes and recently made statement. In addition, numerous burning of houses, gang rape and killing were documented by the UN bodies and international rights groups, which are now undeniable.

Although the state counselor has not yet officially given clarification on the government’s position to be presented at the ICJ, the ruling party National League for Democracy (NLD) made statement that the issue at hand is viewed from the perspective of sovereignty and nation-state point of view.

Very recently, Dr Myo Nyunt spokesperson of the NLD told the media that party leader and State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi would personally fly to The Hague and appear before the ICJ to clarify her earlier silence on northern Arakan conflict issue. He also accused, without naming, that it is a plot of rich countries together with international law experts to put Myanmar in a bad light.

Besides, trying to look at the culprit behind the scene, it is hoped that this will not become a tradition of interfering in the sovereignty of a state, said Dr Myo Nyunt.

“From the departed hundreds of thousands (some 700,000 Rohingya) only few have returned. Before the return of a few, there was not even one returning. I see this from such a multitude of people that left the country, the point that no one returned indicated these people are being controlled and made use until they reach their goal in propping up (their goal) with legal approach,” he said.

“This shows the insincerity. By trying to look at the culprit from behind the scene, I hope the interference of a country’s sovereignty easily will be rejected by people of the world,” he added.

In sum, it could be taken that the ICJ lawsuit against Myanmar is largely seen by the NLD from sovereignty point of view and a sort of phobia that the Rohingya will ask for automatic citizenship rights, including the acceptance of being included into over a hundred recognized ethnic groups as indigenous or Taingyinthar in Burmese, and even territorial rights of their own in northern Arakan State. Then this would ultimately means infringing upon territorial integrity of Mynamar, so goes the argument.

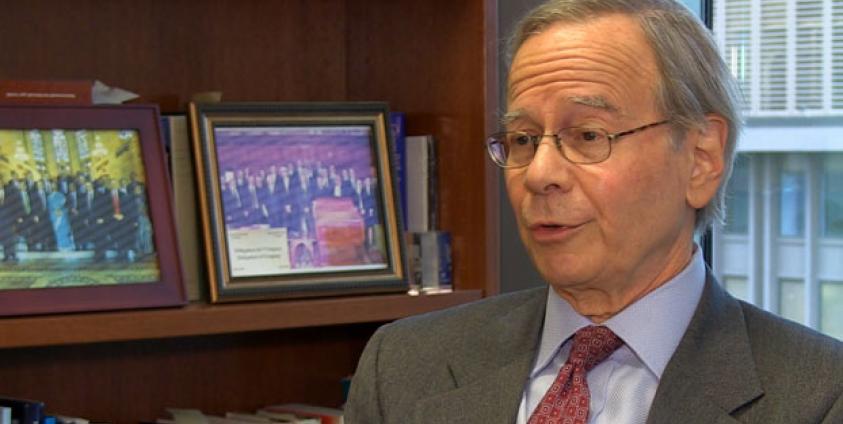

On November 21, Paul Reichler, an attorney at Foley Hoag LLC in Washington, who is assisting Gambia with its lawsuit against Myanmar for state-sponsored genocide at the U.N.’s top court ICJ, told RFA’s Myanmar Service that there are plenty of evidences to win the process.

“There are many, many fact-finding reports by U.N. missions, by special rapporteurs, by human rights organizations,” Reichler said.

“There is satellite photography, and there are many, many statements by officials and army personnel from Myanmar which altogether show that the intention of the state of Myanmar has been to destroy the Rohingya as a group in whole or in part,” he said.

“And we’re very confident that at the end of the day the evidence will be so compelling that the court will agree with The Gambia,” he said, according to the RFA.

Ultimately, the argument of whether the “Rohingya” ethnic identity should be recognized as indigenous is an issue which stem from different interpretation of the recent history.

The powers that be is determined to erase the Rohingya ethnic identity tag as it was a recognized ethnic groups during the tenure of U Nu in the 1960s. The logic here is that if the ethnic identity is accepted all Rohingya will be recognized as an ethnic group and thus all will automatically become citizens, which goes contrary to the desire and notion of the government that all Rohingya are Bengali and illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, which formerly was known as East Pakistan.

In contrast, the Rohingya sees themselves of stemming from ancestors that have been the inhabitants who for hundreds of years have lived in the areas they are now residing.

Apart from that the 1982 citizenship law stipulates that to be indigenous, the ancestors have to be in Myanmar at least starting from 1823, the first Anglo-Burmese war, which is not easy to prove even for the bona fide other ethnic citizens living in the country today.

Thus, even this argument that Rohingya ethnic group doesn’t exist and is a newly constructed identity by the powers that be in Naypyitaw is based on sovereignty point of view, which is an illegal immigrant stigma pressed upon the people it called “Bengali” instead of “Rohingya”, which is desired by the ethnic group.

However, the immediate issue at hand is whether Myanmar is guilty of being a state-sponsored genocide. And in this respect, the state counselor legal team will have to convince the ICJ jury that it is otherwise.

In practical terms, it would mean that the state counselor will have to continue to toe the line that what the Tatmadaw has done is in line with protecting sovereignty and area clearance of cleansing the Rohingya are in order.

Of course, she could also plead guilty and accept the court guidance to do reform, especially on the human rights facet to be in line with universal human rights norms.

Given the overwhelming evidences it will definitely be an uphill battle to refute the allegations. But in the end, Myanmar either has to do the soul-searching why it has to be at the receiving end of the international ire and condemnation or stubbornly cling to its notion of trying to protect its sovereignty and has done nothing wrong to cause the exodus of the Rohingya.

If legal team chooses to do soul-searching, accepts repentance for neglecting state’s responsibility to hinder genocide and work with the international community to redress the harm inflicted upon Rohingya and other ethnic nationalities, the country will be able to get out of the mess it is presently in and able to end the civil war and ethnic strife. But if it chooses to cling to resolving the conflict from the point of only protecting sovereignty, closely linked to illegal immigrant labeling of the Rohingya or Bengali, the international condemnation will go on. And consequently, other international and trade relationships will also be severely affected.

Hopefully the state counselor-led legal team will make a profound choice in The Hague in December.