On October 16, Forest Trends, a non-profit Washington-based organisation established since 1988, with the funding of Joint Peace Fund, released a 72-page important report titled, “Natural resource governance reform and the peace process in Myanmar,” written by Kevin Woods, which emphasizes that the ongoing peace negotiation process directly address the governance of natural resources to realize resource federalism.

Regarding this, the report wrote: “The federal decentralization of land and resource governance on the other hand, if managed well with a full set of integrity mechanisms, could be a means of addressing grievances in many of Myanmar’s resource producing areas.”

“Decentralization generally fails to help locals unless accompanied by appropriate governance mechanisms to ensure compliant implementation – meaning that more focus on and support for resource governance institutions and mechanisms is needed. The extractive sector could act as a driver of more equitable socio-economic development that helps provide greater stability during the post-conflict transition,” explained the report further.

With the formal peace negotiation process between the government of National League for Democracy and the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement-Signatory-Ethnic Armed Organizations (NCA-S-EAO) stalled for over a year since last year July, this report gives an important concrete suggestion that the natural resource governance reform needs to be included in the negotiation agenda, to alleviate some of the many causes of ethnic conflict.

The report pointed out: “Of the 15 existing bilateral ceasefires in Myanmar, only five address natural resources. Rather than reform their governance, the ceasefire agreements simply allow EAOs to continue resource exploitation and revenue generation. In the multilateral Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA), only two clauses mention issues related to land and natural resources which fall far short of what is needed: 1) avoiding forcible land confiscation in favour of land tenure security (§9), and 2) supporting environmental conservation and community consultation in the planning of projects impacting civilians in ceasefire areas (§25). The future Union Accord peace principles have only twelve points that address land and environment, but these mostly assert centralized government control.”

The 72-page report includes seven chapters from “Introduction” to “Conclusions and Recommendations” of which, “Stakeholders’ Positions in Natural Resource Governance Reform and the Peace Process; Resource Governance Decentralization Models; International Environmental Governance Frameworks; and Implementing Steps of Environmental Peace-building are systematically arranged.

Regarding the chapter “Stakeholders’ Positions in Natural Resource Governance Reform and the Peace Process,” various actors’ postures are outlined by the report as below.

Union government

According to the report, “Myanmar’s military and government structures are highly centralized within a unitary state system. Ministries of Defence, Home Affairs, and Borders Affairs are appointed directly by the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services (the Tatmadaw) – not the head of state. Although Chief Ministers of the states and regions are approved by the state/region Hluttaw (parliament), all state and region-level ministers are centrally appointed by, and ultimately accountable to, the Union government and President, as detailed in the 2008 Constitution (Article 261(c)).”

This structure is also enshrined in the 2008 Constitution, preventing ethnic populations from managing their own territories and resources or determining development policy, entrenching decades of exclusion and discrimination.

The 2008 Constitution enshrines centralized state ownership and control of land and natural resources by the Union government.

“Section 37(a) states: “The Union is the ultimate owner of all lands and all natural resources above and below the ground, above and beneath the water and in the atmosphere.”

Section 37(b) states: “The Union shall enact necessary law to supervise extraction and utilization of State owned natural resources by economic forces.”

Moreover, the Constitution does not legally recognize customary authority, land or resource ownership or use rights, nor customary land and forest use management practices (such as shifting cultivation or agroforestry).”

Ethnic Armed Organizations and Institutions

In August 2016, EAO signatories gathered the month before 21st Century Panglong – Union Peace Conference agreed to a platform of eight principles in drafting a new “federal union” constitution. Later, in mid-2017, more than 60 representatives of EAOs – both signatories of the NCA and non-signatories – agreed to what they called basic guidelines to work towards the future establishment of a Federal Union in Myanmar.

Political federalism, as EAOs and EAO blocs argue, would, in general, offer a political arrangement that essentially works to decentralize power and decision-making to the subnational administrative level that would enable ethnic nationality populations to have a greater say in their own state’s development, be more resonant with the local cultural traditions and local communities’ development aspirations, and accrue more material benefits to the local populations.

Political and fiscal federalism also deeply concerns land and natural resource sectors. Ethnic civil society and EAO leaders are demanding ownership and a greater say in the management of natural resources and the sharing of revenue (and other benefits) generated from their exploitation. These positions are key demands being made by EAO leaders in the ongoing ceasefire and peace negotiations.

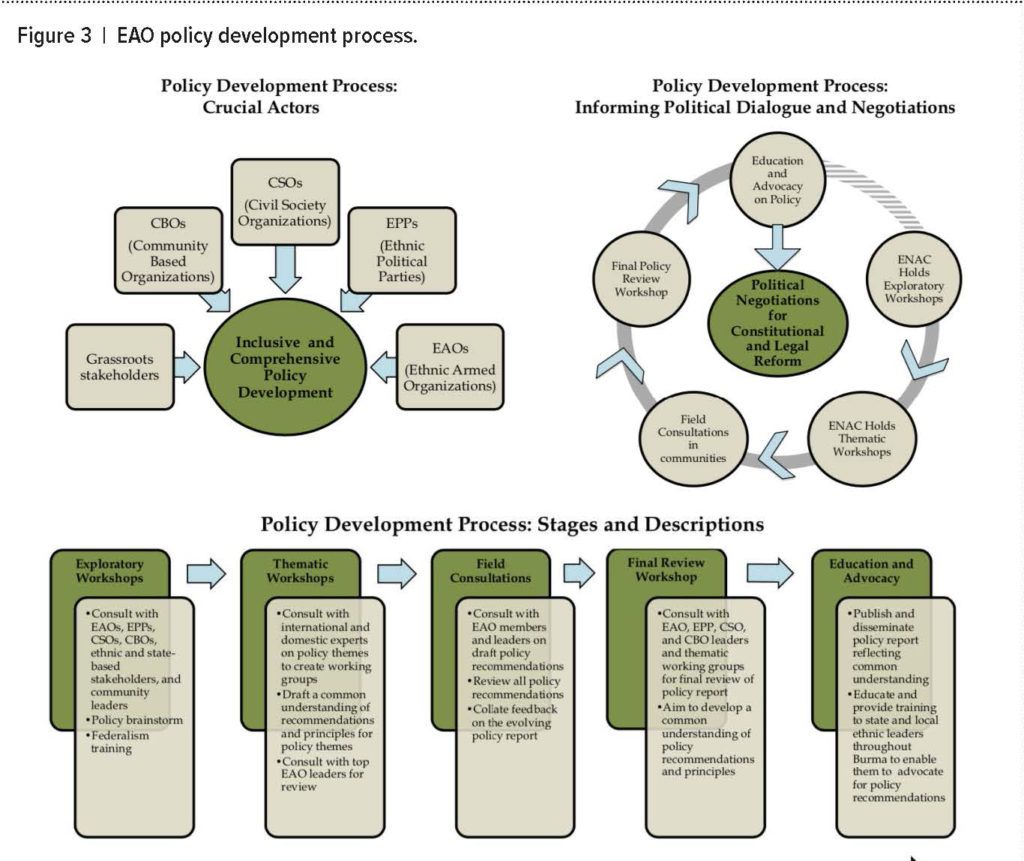

Some EAOs and EAO blocs have established formal policies related to land and natural resources.

Several of the more well-established EAOs, such as the Karen National Union (KNU), Kachin Independence Organizations (KIO), New Mon State Party (NMSP), and Karenni National Progressive Party (KNPP) have set up systems and departments to govern and administer territories, land and resources, and populations under their influence. These generally recognize and complement customary management practices, and provide culturally-appropriate service provision, such as health care and education. Several EAOs also have forestry and agriculture departments that manage land and natural resources under their territorial jurisdiction.

EAOs cover a wide range of politics and territories, the nature of which shapes how EAOs engage with the natural resource sector and their exploitation.

Ethnic civil society leaders and organizations are the most active constituency in Myanmar championing natural resource governance reform, and that this be a key aspect of the peace process and political federalism.

Democratic reforms have led to the emergence of ethnic political parties (EPPs), whose prominence has grown along with ethnic minority dissatisfaction with the NLD administration as evidenced by the elections in 2015 and the 2017 by-elections. EPPs have thus far espoused similar sentiments as those expressed by EAOs and ethnic Civil Society Organizations, wrote the report.

Conclusions and recommendations

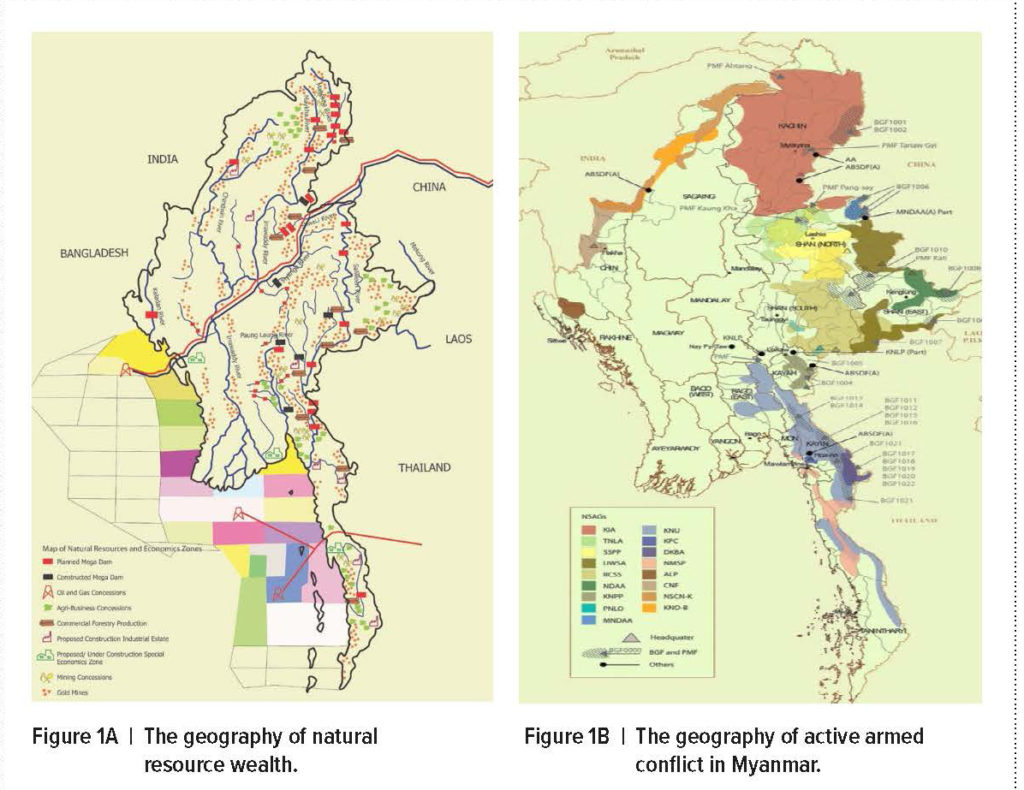

In the report conclusions and recommendations, it wrote: “Natural resources, including timber, gems, oil and gas, and hydro-power, are the mainstay of Myanmar’s economy, generating billions of dollars each year. They are also inextricably linked to Myanmar’s history of armed conflict, in which parties to the conflict have fought (and in many cases, still fight) over the right to control and benefit from these valuable resources, many of which are located in or transported through conflict-affected territories.”

“But instead of resource exploitation driving violence and armed political conflict, natural resource governance reform holds promise for improved prospects for peace – but only if reform addresses these drivers of conflict,” it pointed out.

The benefit of doing it right will be richly rewarded argued the report, saying: “Where natural resources are properly governed, sectors such as forestry and extractive industries can create jobs, boost local economies, mitigate climate change, strengthen local use and ownership rights, and raise revenues for public services such as health and education.”

Analysis

Given such discrepancy in political posture between the government and the EAOs, it is a tall order to find solution to the variety of conflict occurrences. But by all means a compromise have to be worked out if the peace process is to be restarted.

And at this juncture, integration of the natural resource reform could be a spark, which is actually a part and parcel of the political and fiscal federalism. Besides, if the aspirations of a federal union is to be completed, the security sector reform, which is a taboo theme until lately will have to be included.

In this respect, the latest good news making the rounds is that the government, military or Tatmadaw and the signatory EAOs have agreed for discussion on the topic of a “multi-ethnic army” formation, during the meeting in Naypyitaw on October 15 and 16.

As suggested by the report if the natural resource reform could become an integrated agenda in the NCA-based peace process, a lot of conflict causes can be resolved and put to rest. Of course, as the report recommended, the international governments and donors’ support; national and subnational government active participation with political will; EAOs and EAO-affiliated institutions, including the Civil Society Organizations earnest involvement; and national peace process structures and institutions cooperation and coordination will be duly needed.

Hopefully, the planned fourth anniversary NCA and the Joint Implementation Coordination Meeting, the highest organ in NCA-based peace process, will pave the way for a more comprehensive and holistic peace plan that would cover all the main cause of conflict.