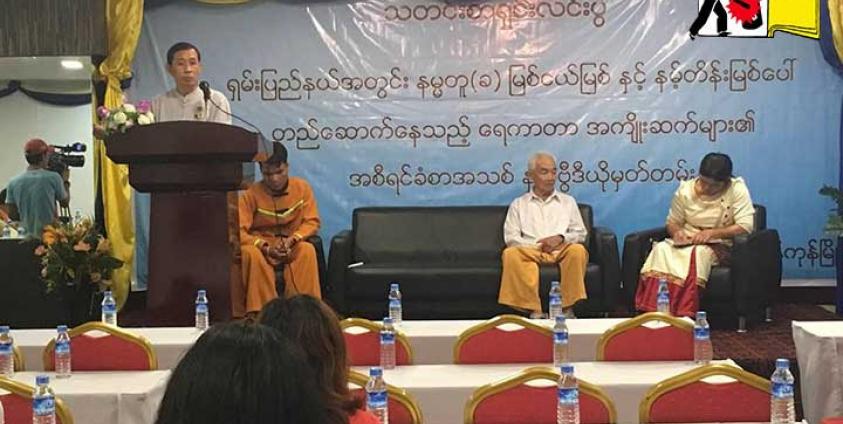

On December 5, Shan communities and local Members of Parliaments held a press conference in Yangon, City Hotel, to call for an immediate cancellation of the Upper Yeywa dam on Namtu river in northern Shan State and the Upper Kengtawng dam on Nam Teng river in southern Shan State, citing devastating social and environmental impacts which will inflame the ongoing conflict.

Both dams, still under construction, were started under the previous military regime, without informing or consulting local communities, and lie in heavily militarized conflict zones. Villagers in Hsipaw – where fighting rages until today — have repeatedly petitioned to stop the Upper Yeywa dam on the Namtu (Myitnge) river, but efforts by Shan MPs to oppose the dam have been voted down in the Naypyitaw parliament.

The first Kengtawng hydro-power project was completed in 2009 forcefully against the local communities’ protest under the military regime of SPDC. But due to shortcomings of engineering it produces only a fraction of the power intended. And now the planned Upper Kengtawng dam is poised to have much greater negative impacts, threatening the health and livelihoods of thousands of villagers downstream in eastern Mong Nai and Larngkhur.

Photo by – SHAN

Upper Yeywa dam

The Upper Yeywa dam is being built on the Namtu/Myitnge river in Kyaukme Township. The planned reservoir will stretch for over 60 kilometers, and is expected to submerge the village of Talong, with 653 inhabitants, temples, pagodas, and schools, as well as 258 hectares of orchards, 57 hectares of rice fields, and countless hill farms.

The project was started in 2008 and is expected to be completed in 2020.

The Upper Yeywa dam project is one of four controversial dams planned on the Namtu River, which is an active conflict zone. Companies from China, Japan, Switzerland and Germany are involved in the project.

Upper Kengtawng dam

The Upper Kengtawng dam is being constructed about 40 kilometers upstream of the existing Kengtawng hydro-power project. It will be a 57 meter high rock-fill dam, creating a reservoir about 15 kilometers in length. It is planned to have an installed capacity of 51 megawatts, although actual production is likely to be far less, judging from the inefficiency of the existing Kengtawng project.

The project begun in 2009, under the former military regime – the State Peace and Development Committee (SPDC). It is solely funded by the Ministry of Electricity and Energy . Norway’s Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE) has assisted with dam design, through the Norwegian engineering firm Multiconsult , which is also involved in the planned Middle Yeywa dam in northern Shan State.

A Chinese state-owned company, China National Technical Import and Export Corporation (CNTIC), will supply generators, turbines and machinery for the project, under an MOU signed with the SPDC in Naypyitaw in April 2010.

There are about 1,800 workers at the dam site, hired from central Burma. They are employed by Burmese construction companies, including Minn Anawrahta Co. Ltd, Dragon Emperor Group, Myanmar Phan Khar Myae Co. and Myanmar Chancellor Co. A Burma Army outpost at the dam site provides security. The dam is slated for completion in 2020-2021.

Feared impacts and concerns

According to the survey of Shan Human Rights Foundation and Shan Sapawa Environmental Organization report “From scorched earth to parched earth” feared impacts due to the damming of Nam Teng, one of the main Salween tributaries in Shan State, are many.

Parched earth: Water flow from the dam will inevitably be reduced in the dry season, as water will need to be stored to produce electricity. This will impact thousands of downstream farmers relying on the Nam Teng for irrigation of riverside fields in the dry season, when river levels are already at unprecedented low levels.

Health risks due to changed water quality: The quality of the water stored in the reservoir, containing large amounts of rotting submerged vegetation – as well as toxic pesticides and herbicides washed down from upstream – will change dramatically from its natural state. Communities living downstream of dams in other parts of Burma have described how water released from dams is “dirty” and “bad-smelling” and has caused fish to disappear and affected people’s health.

And aside from further decrease in fish stocks; disappearance of waterfalls; and fear of dam breakage, due to recent dam breakages – in Laos in July 2018, and at Swa in central Burma in August 2018 – have fuelled fears about the stability of the Upper Kengtawng dam. If heavy rain were to cause the dam to break, the lives of over 8,000 people living in the Kengtawng valley directly below the dam would be at risk. Local residents have little confidence in the dam’s construction standards, knowing that government authorities have never prioritized their safety and interests in developing the project, wrote the two Shan rights organizations.

But the main thrust of the report’s message is to do away with the centralized energy planing and foreign investment that is fuelling the conflict.

“The Upper Kengtawng dam is one of fifty large dams planned by Burma’s Ministry of Electricity and Energy, under an energy master plan aimed to increase national hydropower capacity from just over 3,000 megawatts to 45,000 megawatts, mainly for export to neighbouring countries. Most of the planned dams are located in ethnic states, where decades-long conflict is continuing between the government army and ethnic resistance forces. With central exploitation of their natural resources being one of the key grievances of the ethnic peoples, the government’s insistence on proceeding with these dams is directly fuelling war,” argued the report.

And despite all the negative impacts environmentally, poor economic feasibility outlook and programmed devastation affect on the local population they have not deterred foreign hydro-power investors – both private and state-owned – from seizing on the opportunity to partner with the Myanmar government and its military in building dams in war zones.

The report conclusion spelled out: “Hydropower investment in Burma (Myanmar) has in recent years increasingly come from Western countries, who claim to be supporting Burma’s “peace process”. The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation is clearly supporting the interests of investors over local communities, and ignoring conflict risks. Their recent Strategic Environmental Assessment of Burma’s hydropower sector, funded by the Australian government, identified the Nam Teng basin as a “priority sub-basin for hydropower development,” despite giving it a “very high” conflict rating.”

Adding to this is the report’s portrayal of the Myanmar regime’s mass forced relocation campaign in southern Shan State in 1996-1998, involving widespread rape and killing, depopulated areas along the Nam Teng, that paved the way for large-scale Burma Army expansion and dam-building.

As such, dam-building in central Shan State especially has more to do with intended disruption or subjugation of Shan sense of national identity, cultural heritage and national unity, as it is deliberately planned by the Bamar-dominated government, believed many of the Shan patriots, even though it could also be written off as being just a conspiracy theory.