While Myanmar is faced with it biggest woe of having to appear before the International Court of Justice on charges of state-sponsored genocide scheduled to take place in The Hague, Netherlands, another hard-hitting report of Amnesty International (AI) titled, “Caught in the middle”: Abuses against civilians amid conflict in Myanmar’s northern Shan State,” detailing harrowing conditions of civilians arbitrarily arrested, detained and tortured by the military, added up to the country’s woes that also need immediate attention.

The 44-page report, which has seven chapters includes: background; violations by the Myanmar military; abuses by ethnic armed groups; landmines and explosive remnants of war; and displacement and humanitarian restrictions; among others.

Shan State the largest of all states and regions in the country, bordering China, Thailand, and Laos, it is home to around 5.8 million people, which includes a diverse range of ethnic and religious groups. Shan State’s huge size is often referred to in terms of three separate regions – northern Shan State, eastern Shan State, and southern Shan State.

The AI report is specifically focused on northern Shan State. It documented war crimes and other military violations against ethnic Kachin, Lisu, Shan, and Ta’ang civilians during two field missions to the region in March and August 2019.

“The armed conflicts in northern Shan State are complex, involving the Myanmar military – also known as the Tatmadaw – and a large number of ethnic armed groups. Among these are the Arakan Army (AA), the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), which together operate as a loose grouping known as the “Northern Alliance”. Two ethnic Shan armed groups – the Shan State Army-North (SSA-N) and the Shan State Army-South (SSA-S) also operate in northern Shan State, though the latter’s presence in the area is heavily contested. In recent years SSA-N and TNLA fighters have fought alongside each other, while the SSA-S is loosely aligned with the Myanmar military. In May, the SSA-N and SSA-S announced a mutual ceasefire, however this did not include the TNLA, which sporadically clashes with the SSA-S. A number of military backed militias and paramilitaries also operate in the region,” according to the AI report.

On 12 December 2018, the political wings of the AA, MNDAA, and TNLA announced that they would halt military operations and engage in political dialogue. Then on 21 December 2018, the military announced a unilateral ceasefire. Initially limited to six months, the ceasefire covered five regional military commands in northern and eastern Myanmar, however did not include Rakhine State in the west of the country. The military has thrice extended the ceasefire – for two months from 30 April and again from 30 June, and most recently for 21 days on 31 August. On 23 September, the military confirmed the ceasefire had ended, accusing the ethnic armed groups’ lack of interest in signing the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement.

Even then, human rights violations occurred increasingly in northern Shan State as the armed conflicts have never really stopped despite the Tatmadaw’s unilateral ceasefire, prompting the AI to accused all warring parties of human rights violations against the civilian population.

Civilians who spoke to Amnesty International repeatedly implicated the military’s 99th Light Infantry Division (LID) in many of the violations. Units from the 99th LID were implicated in some of the worst atrocities against the Rohingya in Rakhine State since August 2017, as well as in war crimes and other serious violations in northern Myanmar in 2016 and early 2017.

“Wherever the 99th Light Infantry Division is deployed we see similar patterns of abuse and the commission of horrific crimes unfold. This highlights the urgency of international action to hold Myanmar’s military – not least its senior generals – accountable.”

AI’s research found that the Myanmar military subjects civilians to arbitrary detention, often arresting men and boys on the basis of their ethnic identity and a perceived link with a particular armed group. Arrests and detention were often accompanied by torture and other ill-treatment. Soldiers beat, kicked, and punched detainees in order to obtain information about ethnic armed groups, or else to force detainees to “confess” to being members of such groups.

In one incident in March 2019, Myanmar soldiers forced a 35-year-old ethnic Kachin fisherman to squat semi-naked with a grenade in his mouth after accusing him of links to the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). He recalled one of the soldiers asking, “‘Are you KIA?’ I said ‘no’, then they started punching and kicking me. They forced me to take off my clothes [and] held a knife to my neck… They put a grenade in my mouth. I was afraid if I moved it would explode”.

In some cases, detainees were taken to military bases where they were held for up to three months, usually held in incommunicado detention. In one case, a man and a 14-year-old boy were made to undertake forced labour while on a military base in Kutkai town, home to several units from the military’s Northeast Command.

AI’s research also found that the military has fired indiscriminately in civilian areas, killing and injuring civilians and damaging homes and other property. Myanmar soldiers also shot and killed a 17 year-old ethnic Ta’ang boy in Kutkai Township, suspecting him of being a member of an ethnic armed group in February 2019. In another incident, a 17-year-old ethnic Kachin boy was injured by a mortar shell which was likely fired by the Myanmar military during fighting with the TNLA in early August 2019.

Myanmar soldiers also regularly move through – and at times stay in – villages, exposing civilians to the risk of attack. At times Myanmar soldiers also confiscated property, taking foodstuffs such as chicken and rice from civilians while using their homes and villages as temporary shelters and bases.

The ethnic armed groups also commit abuses against civilians, in particular in areas where there has been intense fighting among armed groups during the military unilateral ceasefire. Fighters from ethnic armed groups have abducted civilians – usually men – or otherwise deprived them of their liberty, usually accusing them of supporting a rival group. Civilians were often beaten in order to obtain information about the other groups, as an ethnic Shan man, who was one of two villagers detained by the TNLA and SSA-N in March 2019, explained: “They accused me of being SSA-S and giving information and food to SSA-S soldiers… They tied our hands [and] beat my back and thighs with sticks… I kept saying, ‘I am just an ordinary citizen, I am not in favour of any armed group’.”

Other than that ethnic armed groups have also subjected civilians to forced labour, including forcing them to act as guides and engaged in widespread “taxation” and extortion, demanding money and food from villages and businesses.

The proliferation of conflicts in the area has come with an alarming increase in the number of civilians killed or injured by landmines, improvised explosive devices (IEDs), or other explosive remnants of war (ERW).

Credit : reliefweb.int

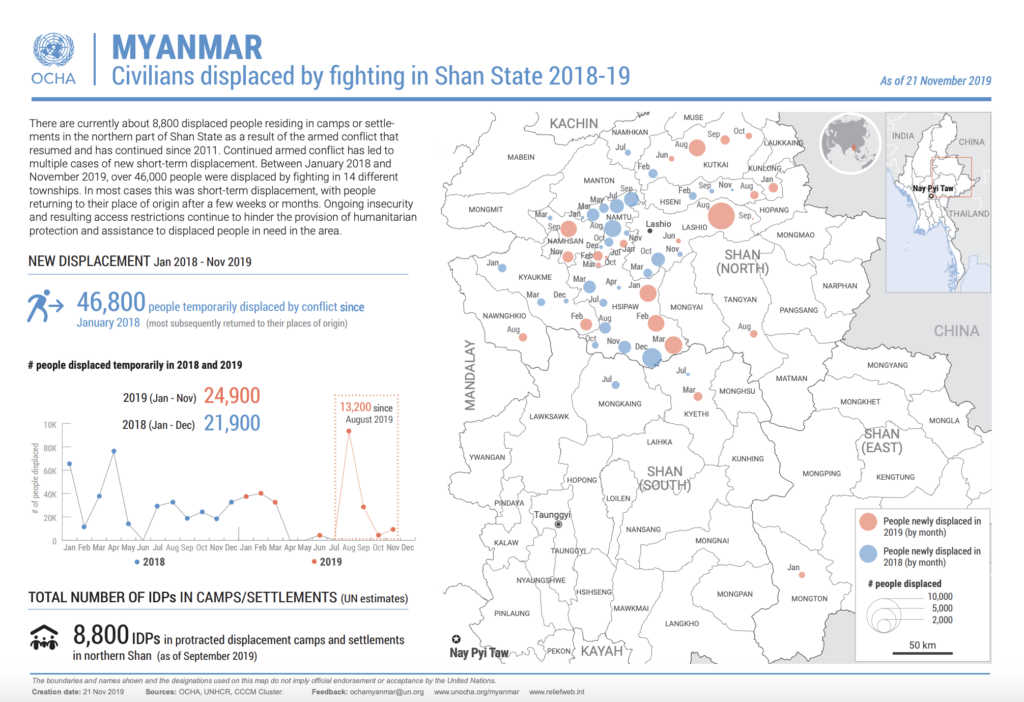

The ongoing conflicts have also led to repeated displacement of civilians. But unlike in other parts of Myanmar where long-year displacement are common, in northern Shan State, they tend to be displaced to makeshift sites for shorter periods – sometimes a few days, sometimes several weeks, sometimes longer – and then return to their homes and farmlands when the fighting has moved on to another area. The irregular but continual nature of this displacement poses challenges for humanitarian organizations working to provide aid and assistance and short-term displacement also has an adverse impact on livelihoods, in particular when people are displaced from their homes at key points within the land cultivation cycle.

“The situation highlights yet again the need for international action to ensure that those responsible for serious crimes in Myanmar do not continue to enjoy impunity. The UN Security Council, which for too long has stood by as civilians were abandoned to a ceaseless cycle of violence, must fulfil its responsibility and refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court (ICC),” wrote the AI report.

The Tatmadaw, TNLA and the RCSS have all told the media in response to this AI report that they have tried to educate their troops not to commit human rights violations against the civilians. But confessed that it was an uphill battle and more have to be done.

“We will not refute these accusations since this is not the first time [we have been accused]. Instead, we will only talk about what the military has done in response to the alleged human rights violations,” said Brigadier General Zaw Min Tun spokesperson from the military’s true news information team.

“We have been taking actions against military personnel when they commit rights violations or break the law,” added the spokesperson.

Accordingly, the military’s legal division has been working on providing education to soldiers on human rights violations and laws related to military activities, which is necessary to build a modern fighting force, the recent RFA report wrote.

But the statement of military spokesperson runs contrary to the human rights violations in Rakhine State which are widely reported.

Likewise, TNLA spokesperson Colonel Mei Aik Kyaw also denied that its organization used forced labor, arbitrarily arrested people or tortured them.

“We don’t have any policy, nor have we ever given orders to use [forced labor,]” he said.

“We don’t know where [Amnesty International] gathered the data to make these accusations,” he added.

In the same vein, RCSS spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Sai Oo on October 1 told the RFA: “We have educated our troops on human rights. Our officers are also controlling our troops on the ground.”

While such half-hearted commitment to adhere to human rights and educating their troops on the ground by all warring parties about universal human rights norms won’t bring any immediate result for the local population, the ICC deliberation approach will not also bear fruits anytime soon. The only hope left to lessen the local population’s burden and suffering is to end the armed conflict as soon as possible and this is also nowhere in sight for the time being.