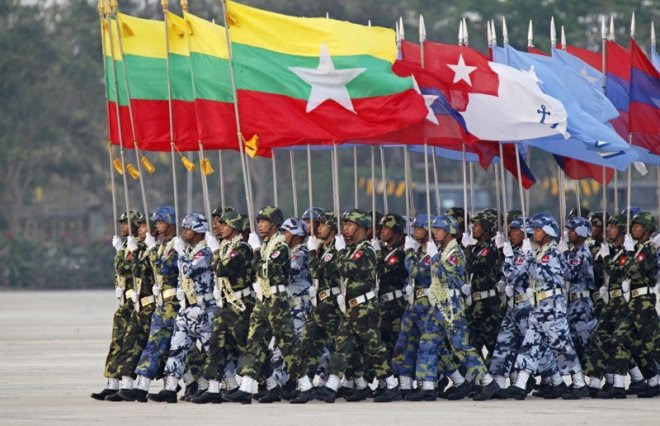

The transformation of Myanmar’s “all-powerful” military to one that accepts democratic constraints on its power will be an enormous challenge, the International Crisis Group says in a report released on April 22.

In the report, Myanmar’s Military: Back to the Barracks?, the Brussels-based think tank examines the Tatmadaw’s key role in political and economic reforms.

It says that for a “full democratic transition” to take place in Myanmar, the Tatmadaw needs to accept that its political role, as enshrined in the constitution, must be reduced and civilian control of the armed forces increased.

The report’s major findings and recommendations include an acknowledgement that the reform process in Myanmar is a consequenceof theTatmadaw’s seven-point roadmap for a transition to democracy unveiled by the ruling junta in August 2003.

“It is sometimes wrongly assumed that the military is the main brake on reform, or its potential spoiler,” says a news release accompanying the report.

“Myanmar’s political transition has been top-down; the military initiated the shift away from dictatorship,” it says. “The military has generally been supportive of political and economic reforms, even when these have impacted negatively on its interests, including through loss of power, greater scrutiny and loss of economic rents.”

The ICG says the military initiated the transition because it “saw a significant threat from the country’s increasing dependence (both political and economic) on China and because economically Myanmar was falling dangerously behind even its poorest neighbours”.

The military believed the only viable responses were to counterbalance China’s influence and open up the economy, “for both of which improved relations with the West were indispensable,” it says.

One of the report’s recommendations focuses on the Tatmadaw’s poor human rights record.

“The military must end rights abuses and change how it interacts with civilians, particularly in the ethnic borderlands, in order to restore its damaged reputation and transform itself into a professional institution that is reflective of – and serves to defend – Myanmar’s ethnic and religious diversity,” says the ICG.

“While the military proved more integral to Myanmar’s reform than perhaps many anticipated, its role in the country is still problematic,” said the ICG’s acting Asia director, Jonathan Prentice.

“It needs to transcend decades of dictatorship and internal armed conflict and move from being seen as the oppressor, or enemy, to being a respected national institution,” Mr Prentice said.

“If the military hangs on to its constitutional prerogatives for too long, it will be detrimental to the democratisation and future prospects of the country,” he said.