Thank you for being here this morning, and I want to thank our Chargé and the U.S. Embassy for all of their support. It is a true pleasure for me to return to this country after 15 years. It is one of the most beautiful places in the world, full of decent, amazing people who inspire me every day. It is wonderful to be back.

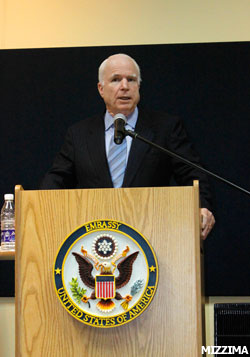

The following is the official transcript of a statement by US Sen. John McCain released at the end of his official three-day visit to Burma.

Senator John McCain

June 3, 2011

Rangoon, Burma

Thank you for being here this morning, and I want to thank our Chargé and the U.S. Embassy for all of their support. It is a true pleasure for me to return to this country after 15 years. It is one of the most beautiful places in the world, full of decent, amazing people who inspire me every day. It is wonderful to be back.

US Sen. John McCain speaking at a press conference in Rangoon. Photo: MizzimaOver the past two days, I have had a chance to meet with senior leaders in the new civilian government, including both speakers of parliament and the First Vice President. I have met with political opposition and ethnic minority leaders, both in and out of the government. I met with recently released political prisoners, some of whom had been detained for as long as 20 years. I have met a few living saints—men and women who are providing extraordinary and desperately needed services for the poorest people in this country. And of course, I have met with Aung San Suu Kyi, who has been a personal hero of mine for decades, and whose standard of service to her fellow citizens I can only marvel at and seek to emulate.

US Sen. John McCain speaking at a press conference in Rangoon. Photo: MizzimaOver the past two days, I have had a chance to meet with senior leaders in the new civilian government, including both speakers of parliament and the First Vice President. I have met with political opposition and ethnic minority leaders, both in and out of the government. I met with recently released political prisoners, some of whom had been detained for as long as 20 years. I have met a few living saints—men and women who are providing extraordinary and desperately needed services for the poorest people in this country. And of course, I have met with Aung San Suu Kyi, who has been a personal hero of mine for decades, and whose standard of service to her fellow citizens I can only marvel at and seek to emulate.

It was clear from my meetings in Nay Pyi Taw that the new government wants a better relationship with the United States, and I was equally clear that this is an aspiration that I and my government share. The United States is not condemned to have bad relations with any country, as our recent experience with neighboring Vietnam demonstrates. I acknowledge that this new government represents some change from the past, and one illustration of this change was their willingness to allow me to return to this country after 15 years worth of attempts to do so on my part were rejected.

I sincerely hope that there could now be an opportunity to improve relations between our countries, and I stand ready to play a role in such a process where I can be helpful. The United States should be willing to put all aspects of our policy on the table and give fair consideration to the requests this new government makes of us. But as I told the government leaders I met yesterday, any improvement in relations will need to be built not on warm words, but on concrete actions. I and other U.S. leaders, including in Congress, will evaluate this new government’s commitment to real democratic change, and thus the willingness of the United States to make reciprocal changes, based on several tangible actions, as called for by the United Nations Human Rights Council in its Resolution of March 18, 2011.

One critical step is the unconditional release of all prisoners of conscience. Respected international institutions and human rights organizations, including groups in this country, estimate that more than 2,000 men and women are imprisoned here for actions that should not be considered crimes in any country—the exercise of universal human rights and fundamental freedoms, of speech, of thought, of worship, of association, which all governments should uphold. I have asked the new government to grant the International Red Cross immediate and unfettered access to all prisoners in this country, which would help to improve their conditions.

Another step, as called for by the U.N. Human Rights Council, is ensuring the safety and human rights of Aung San Suu Kyi, especially as she seeks to travel around the country in the near future, as she has stated she will. Aung San Suu Kyi’s last attempt to travel freely was marred by violence, and the new government’s ability and willingness to prevent a similar outcome this time will be an important test of their desire for change—for the protection of Aung San Suu Kyi should not be seen as special treatment for one famous citizen, but rather as a demand of human dignity to which every citizen of this country is entitled.

In addition to guaranteeing the rights and freedom of movement of Aung San Suu Kyi, the U.N. Human Rights Council has also urged this new government to begin a democratic process of national reconciliation—a genuine attempt to unite this country through peaceful dialogue. It is the judgment of the Human Rights Council—and I concur with it—that, to be legitimate, such a process of reconciliation would have to involve Aung San Suu Kyi, ethnic minority and other opposition leaders, and the National League for Democracy, which has been recognized before, and should be recognized again, as a legitimate political party.

Finally, the new government must abide by its international obligations to uphold United Nations Security Council resolutions regarding non-proliferation, and to cease any military cooperation with the government of North Korea, as required by international law.

Concrete steps like these need not, and should not, take a lot of time. They could be done quickly, if the new government is willing, and they could be met with reciprocal steps by the United States to contribute to improved relations. This attempt at engagement should be time-bound and results-oriented. And in the meantime, the community of responsible nations should continue to push for a Commission of Inquiry, which has nothing to do with vengeance or retribution and everything to do with accountability and justice for the people of this country.

Similarly, as Aung Sang Suu Kyi herself has stated, without concrete actions by this government that signal a deeper commitment to democratic change, there should be no easing or lifting of sanctions. In fact, we should seek to do a more effective job of implementing existing sanctions. At the same time, let’s not lose sight of what would be the greatest contribution to the development of people here: a commitment by the new government to address this country’s dire challenges of health, poverty, education, and governance with a similar level of tenacity—and resources—that they are devoting to the construction of Nay Pyi Taw.

Ultimately, releasing prisoners of conscience, protecting human rights, and deepening comprehensive reforms are not steps this new government should embrace for the sake of the United States. They should do so because it is the right thing to do. Because it will add to the success of this country and the development of its people. Because it would create an opportunity for a new kind of relationship with the United States—one that will respect and strengthen the independence of this country, not undermine it. And most of all, because the winds of change are now blowing, and they will not be confined to the Arab world. Governments that shun evolutionary reforms now will eventually face revolutionary change later. This choice may be deferred. It may be delayed. But it cannot be denied.

The people of this great country are eager for democratic change, and they have given much to achieve it over many years. If the new government shows itself willing to make a genuine commitment to real democratic reform and economic development, it will find a willing partner in the United States—and in me.

Thank you.