The Sangkhale River sat as a barrier between the two villages on its opposite banks after dam construction in 1981 caused the water level to rise, making an old rope bridge unusable.

Thai villagers on one side and Mon and Karen refugees in Winka Town, across the river, seemed worlds apart because the river was not just a physical barrier to communication and commerce, it was a symbol of the cultural barriers between them as well.

However, Abbot U Ottama, of the Mon temple in Winka, financed the construction of a new wooden bridge in 1984 (Buddhist calendar year 2528), which brought the residents from the two communities together, in more ways than one.

“The water lever was high and the river widened after the Tao Khanon dam was constructed in 1981 (Buddhist calendar year 2525). Therefore, if people wanted to go to the Thai side from Mon side or from the Mon side to Thai side, they had to cross the river by boat or a raft. The crossing was dangerous and some died in the river. As well, people had to pay the boat fare. Therefore, Abbot U Ottama constructed the wooden bridge to make the journey safer,” a monk lecturer at the Winka temple said.

A total of 170 tons of wood were provided by the Thai Ministry of Forestry to be used in the construction.

The difficult journey had limited business opportunities between the communities before the construction.

“Most people in Mon side have grown vegetables. In the past, these farmers had very small market for their vegetables because there was no bridge to cross the river. So, they could only sell vegetables in their own village. After the bridge was constructed across the river, these farmers could cross the river easily and they could sell their vegetables on the Thai side,” Mi Kon Kye, a vegetable vendor, said in a recent interview.

It also limited social interaction and communication.

“The Thai and Mon sides seemed to be two villages because they were separated by the river,” according to Nai Aung Sein, a 79 year-old Mon, who worked on the construction.

“There was not much of a relationship between the two communities. Now, the relationship between the two communities is very good because of the wooden bridge,” he said.

“There was a lack of friendship between Mons and Thais in the past because these two communities were separated by the Sangkhale River. Their relationship was very cool, even though they lived so close. Young people often fought in the streets in the past. Now, relations have warmed and the two communities have become close. Friendship between these two communities is good,” Saw Hla Shwe, a 60 year old Karen man, said.

The abbot also financed an extensive renovation of the bridge, during a two year project begun in April 2009.

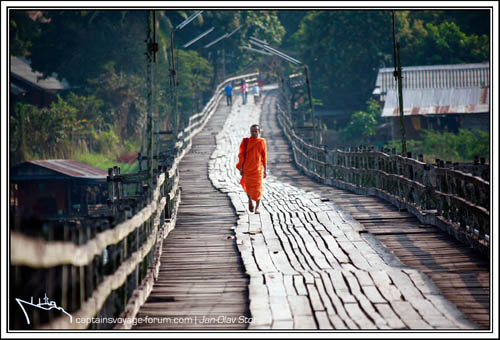

The current bridge is the longest wooden bridge in Thailand at 445.5 meters. It is 4.5 meters wide. The highest section is 35 meters, at the middle of the river.

About 20,000 baht was collected from donation boxes at either end of bridge every day, during the renovation.

“The distinction of the new bridge is that it is built with Pyinkado, Thingan and other hard woods. The pylons of the old bridge were straight up. The pylons of new bridge are not straight up- but a little bit angled and wider at the base. There are four benches opposite each other on the new bridge. Two buildings at either end of the bridge were rebuilt again. The new wooden bridge can be used for at least 20 years,” said architect, Nai Zar Pan, who oversaw a team of 13 carpenters.

Motor cycles and bicycles, as well as pedestrians, were permitted to cross the original bridge. However, only people were permitted to cross the bridge in later times.

Many students from the Mon side cross the wooden bridge daily to attend a high school on the Thai side. Local people say they are pleased to see the students in their school uniforms on the wooden bridge, their energetic movement matched by the beauty of the bridge itself.

Daily laborers, vendors and other villagers cross the bridge frequently. They greet each other on the way back from their respective jobs. Sometimes, they make a joke for each other and laugh on the bridge.

Thai people are proud of the wooden bridge, according to Nai One, a Thai restaurant owner who sells food near the bridge.

Nai Phon, a Thai resident in Sangkhlaburi, said it has fostered economic development for Sangkhlaburi, as Thai and foreign tourists come to town to see the famous structure.

They can be seen taking photos in the early morning light, or enjoying the fresh air in the evening breeze.

“It’s very peaceful seeing the bridge from our boat rowing on the river, which is like a lake. It’s pleasing to see the bridge because it’s constructed with logs,” Mr. Pharon, an American tourist, said .

There are over 50 floating houses near the wooden bridge, which attract about 2,000 tourists per week. About 1,000 more stay in local hotels, resorts and inns.

“Visitors like to stay on the floating houses near the bridge. They want to see people walk on the bridge and enjoy the fresh air. Visitors are pleased to see the crowds of people on the bridge when they are eating nearby or playing in the water,” according to Nai Chit Ngwe, who owns a floating house.

Mon children, who speak English fluently, as well as Mon and Thai, are working as tourism guides on the wooden bridge. These children can explain about the wooden bridge, the local environment and the religious buildings in Sangkhlaburi.

Some visitors buy Mon traditional clothes, flowers made with paper, toys, and post cards with a picture of the bridge and other souvenirs.

Today, the wooden bridge at Sangkhlaburi stands as a symbol of the harmony between the communities it has joined together.