The best would be if this country adopted a more regional perspective, which would be more in line with federalism. So instead of thinking about the big national grid, maybe look at electricity on a regional basis, then support the people in the region where the dam is located. Dams with an output of 600 or 800 MW are medium dams, not small, but something that is realist here, and I think if it is done well, there will be more investors.

Joern Kristensen, Director, Myanmar Institute for Integrated Development, DVB, 19 September 2016

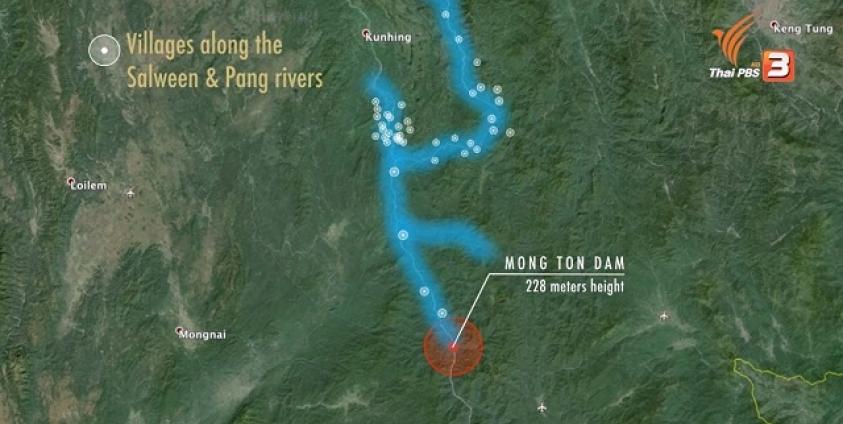

It took me only half an hour to watch Drowning The Thousand Islands, a documentary produced by Action for Shan State Rivers, launched Wednesday, 21 September, on Thai PBS. But it took me the whole evening to look up old papers and reports to understand (or, rather, reeducate myself ) why the people in Kunhing (meaning Thousand Islands) township are so bitterly against the Mongton (formerly Tasang) dam project on the Salween.

After going through them and talking to the exiles from Kunhing, I realized that the reason for their stiff resistance was more than about fear of destruction of their homes by flooding, displacements of their 137 villages and the bulk of power going to neighboring countries instead of setting aside for domestic use.

From 1996 to 1998, the then military government launched a 3 year long forced relocation campaign against the Shan State Army (SSA) South, the group that last year signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement (NCA) with its successor led by U Thein Sein. The drawn out offensive relocated some 1,500 villages in 11 townships, which included Kunhing, resulting in over 300,000 people being displaced and at least 664 of them extrajudicially executed.

According to Maj Aung Lin Tut, a military intelligence officer who later went into exile, it was Senior General Than Shwe himself who issued the order to relocate the villagers, using extreme measures. “Not even 0.25 viss (meaning a fetus) must remain,” the major quoted him as saying. (Voice of America, Burmese Service, 25 May 2008).

According to Maj Aung Lin Tut, a military intelligence officer who later went into exile, it was Senior General Than Shwe himself who issued the order to relocate the villagers, using extreme measures. “Not even 0.25 viss (meaning a fetus) must remain,” the major quoted him as saying. (Voice of America, Burmese Service, 25 May 2008).

Of the 11 townships, Kunhing appeared to have borne the major brunt of the Burma Army’s rampage.

Among those 319 recorded killed in Kunhing alone was a Shan abbot who was tied up in a bag and thrown into the river and drowned. (As if it wasn’t enough, the Burma Army staged two more massacres 2 years later:

24 in Wanphai on 17 May 2000

59 in Hsaimong on 21 May 2000)

Even ghastlier were the rapes, often accompanied by killings. License to Rape, the report by Shan Human Rights Foundation (SHRF) and Shan Women’s Action Network (SWAN), that came out in 2002 to shock the world triggering panick-stricken denials from the authorities, detailed 29 cases of rapes in the township of 117 women, 21 of whom were killed.

The following piece, considered a “mild” case, appears in the report:

Name: Naang Mo (not her real name)

Age: 13

Status: Single

Ethnicity: Shan

Religion: Buddhist

Occupation: Farmer

Location: Nam Kham village, Kunhing township

Date of Incident: August, 2001

SPDC Troops: LIB 246, Kunhing-based

SPDC troops were patrolling the area near Kunhing base, when they saw thirteen-year-old Naang Mo with her fourteen-year-old friend, Naang Jung collectiong vegetable in the forest, two hours outside Nam Kham village. They approached the girls, and Naang Jung managed to escape and run to safety. But a captain caught and raped Naang Mo and then released her near Nar Khue village early the next morning. Just outside Nar Khue village, Naang Mo put face in her sarong and cried. Eventually, she made it back to her village and told her relatives what had happened, They wanted to complain to the local base commander, but they were afraid that, if they were to report the incident, they would be punished with fines or imprisonment. Although they wanted justice, there was nothing they could do.

Obviously, most of the rapes and killings were committed by two of the township based units: Infantry Battalion (IB) 246 and Light Infantry Battalion (LIB) 524. Others on the list include IB 12 (Loilem), IB 64 (Laikha), IB 102 (Ngwedaung), LIB 424 (Hsihseng), LIB 519 (Mongton) and LIB 529 (Tachilek).

It is therefore not surprising that the dam project has run up against such a stiff opposition from the populace, who have been reeling under countless abuses from the government for decades.

Indeed, it wouldn’t be difficult for The Study Times, a Chinese influential paper that, according to Reuters, 19 September, wrote the dam projects in Myanmar were “unreasonably attacked” by some “extreme” Myanmar media, non-governmental organizations and people heatedly opposed to the Myitsone Dam and other large-sale projects on the Salween River, to find out why the projects have become such an emotionally-charged issue.

As for our present government, my counsel is that before it embarks on any mega development project that will make huge impact, in one way or the other on the people, the first thing to do is to heal the wounds, meaning the psychological ones and to give them the parental care that previous governments had deprived them of since the Burma Army invaded in force into the Shan State in 1952.

It’ll be more sensible to talk to them about dams later, but not now.