I could wait for the public transport to take me to the Shan Literary and Culture Society’s Meeting Hall, some 300 meters away.

But the morning was lovely, cool and pleasant. It would be good to revive some long lost memories by taking a solitary stroll down to the main road and across it to the meeting hall, I thought. And I wasn’t disappointed, though I won’t bother you with the details here.

I walked past the Eindaw, now the residence of the Shan State Chief Minister, and through the tall pine trees that I remembered so well. Only now I had to be careful to walk on the right hand side of the road. (Burma, being under British, used to drive on the wrong side but in 1968, Gen Ne Win, during his fight against the communists, was said to have been advised by his astrologers to switch to the right hand side).

The meeting hall is located just next door to Government High School #2, the school I had attended until matriculation.

Hundreds of participants were already there when I arrived. One of them was my childhood friend Sao Yun Peng, now a CEC member of the Shan Nationalities Democratic Party (SNDP), whom I used to know as Gilbert Hti. At the sight of him, I had a mixed feeling: One side of me was glad to see him again after all these years, but the other side was sorry to see he had grown old and bald: Well, I reminded myself, I wasn’t getting younger either.

The second day of the forum was unquestionably Lawyer Ko Ni’s day. I won’t repeat myself because I have already reported on the next day how he had mesmerized the audience with his eloquent arguments about why the 2008 constitution should be dumped in favor of a rewrite.

My own attention was on the Wa and Mongla representatives’ presentations. While Xiao Hsarm Khun, the United Wa State Party (UWSP)’s deputy head of external affairs, made himself conspicuous (at least to me) by not reiterating his call for a separate Wa state, Kham Mawng, the chief public relations officer of the Mongla-based National Democratic Alliance Army (NDAA), so far reticent about his group’s aim, was coming out of his shell by demanding for a “special status” to its domain along the Sino-Burmese border alongside the Wa.

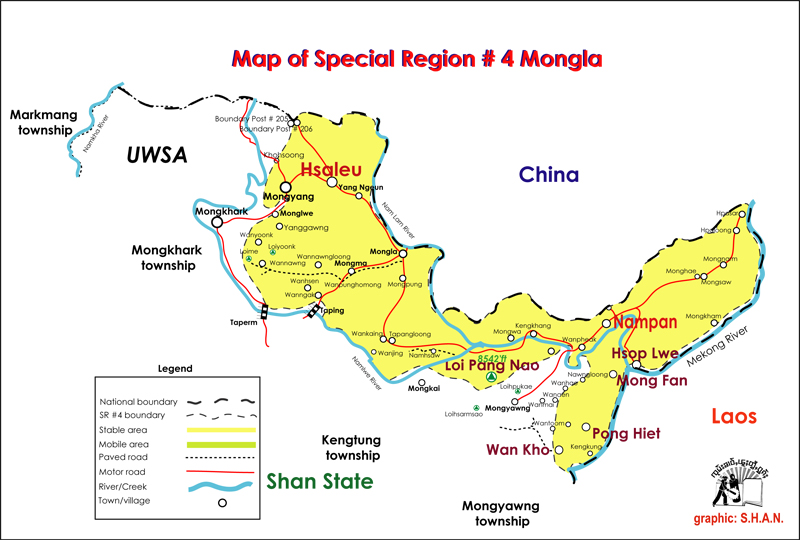

Mongla itself is now designated a separate township. But its Hsaleu village tract in the northwest and Nampan village tract in the southeast have been named parts of Mongyang and Mongyawng townships respectively. Losing them would mean Mongla would be cut off from its Wa allies (who would also be cut off from it) and surrounded on all sides by the Burma Army (with the same result for the Wa).

“Without first reaching an acceptable political solution”, one NDAA official told me earlier, “we are not going to let that happen.”

Another noteworthy presentation, maybe scarcely noticed, was read out by Brig-Gen Pawng Kherh of the Restoration Council of Shan State (RCSS) who had inserted a recount of the 1996-98 forced relocation campaign launched by the Burma Army.

It was, I thought as I listened, a polite response to the Burma Army’s 6 point in demand August which included: Not to kill civilians.

According to the report published by the Shan Human Rights Foundation (SHRF) in 1998, Dispossessed, over 1,400 villages in 11 townships in Shan State were forcibly relocated. At least 664 of the people were confirmed killed by the Burma Army, with one of them, a Buddhist monk, tied up in a sack and drowned. Hundreds of girls and women had also been sexually abused, which led to the better known report, License to Rape (2002).

At the conclusion of the day’s session, I was picked by my brother-in-law to visit my sister, age 73, who was in hospital. She was weak but in good spirits.

When I was back at the hotel, I thought about what Tony Blair had said in August to Thailand’s leaders on national reconciliation:

“Reconciliation happens when the sense of shared opportunity is greater than the sense of grievance. The past can be honestly examined, but it can never be judged in a way that is going to be the satisfaction of everyone. Reconciliation is never going to be about people changing their mind about the past. It is really going to be about changing their mind about the future.”

I then jotted some notes about what I was going to say to the participants on the morrow and turned in. I went down, as Gavin Lyall once wrote, like a crashed airliner.